Techniques for Printing on Corn Husks, Chapter 12

A Short, Unfair, Unbalanced History of England

Main -- House -- History -- Cornwall -- Getting There -- On the Road -- The Roads -- London -- The Far West -- Boring Details -- Updates

The informed traveler, of course, tries to learn something about the lands he visits. The uninformed traveler, however, can read the following and get the gist of it.

Back at the end of the last ice age, when there was still solid land from Dover to Calais and Frenchmen had not been invented, a few wanderers made their way into Britain. A bit of rising seas and a bit of erosion, and the island known as Great Britain was born. It was a dark, simple, and tealess time, and after a while of hunting and gathering these animal-skin-clad foraging proto-hippies began to settle down into an agricultural lifestyle.

The ancient days of Britain are hard to reconstruct in any detail, but sheesh, they liked to build in stone. Great monuments of the Neolithic period survive here and there to tell us that these were some clever people with some odd hobbies. The Orcadians, up north and not technically in Great Britain, invented the sports mascot, stocking their community tombs with things like eagle talons and dog skulls. Cave bears were fortunately in relatively short supply, as, equally fortunately, were Jean Auel books. The Stone Age ended when, after a lot of flint-knapping and chalk-digging and axe-shaping, a critical shortage of rocks triggered a financial panic. |  |

Then came the Bronze Age. Surviving video of the time (left) suggests that the Bronze Age was not viewed as great progress by many of the stone-age traditionalists, but it came just the same and the quality of grave goods, previously composed mostly of pottery, started to rise. Societies became less egalitarian and more authority-based as early Britons with bronze tools began to smash in the heads of early Britons without bronze tools. |

Somewhere around the Iron Age, a few centuries BC, came the Druids, the first religious group in the island of which we have any written record. And, though you can now find modern Druidic groups who claim to be keepers of the ancient mysteries, mostly what we really know about the Druids is that the Romans didn't like 'em and pretty well wiped them out. Did they all drive camper vans out to Stonehenge on the solstice like their modern counterparts? Who knows? |  |

Trajan, London Wall; this statue depicts Trajan in the act of hailing to the north: "Yo, Hadrian!" | And then recorded history gets started. The Romans show up, kick the door in, and start building cities and exporting tin, among other things. Hadrian (famous now primarily for the expression coined by Trajan and later resurrected by Sylvester Stallone, "Yo, Hadrian!") built the wall across the north which was supposed to keep Mel Gibson's "Braveheart" out but which instead improbably shows up in "Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves" as a backdrop for Nottinghamshire, quite a long walk to the south (but, according to Kevin Costner/Robin Hood, less than a day's trip from Dover; evidently the filmmakers did not know that Britrail had not been invented yet in those days). After defeating Boudicca, building Bath, and erecting a wall around Londinium, the Romans decided they liked Italy better after all, and left. |

So, around this time might have been King Arthur. Or not. But with the exit of the Romans came the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, invaders from Germany. The previously-Celtic Britons were assimilated into Germanic culture, or fled to the hinterlands of Scotland, Wales and Cornwall, and Germany had its last significant war victory over the British. Celtic Christianity, very popular in Roman times, gave way to the Northern European complex of gods like Woden and Thor for a few centuries, and the Anglo-Saxon warlords had a pretty good run of it for a while until the Vikings started to turn up. |  |

| So, along come the Vikings. They built York (well, the Romans built "Eboracum" there, but what an awful name; the Vikings called it Jorvik, which was a huge improvement), which despite having the country's greatest chocolate factory did not invent the York Peppermint Patty any more than Philadelphia Cream Cheese is really from Philadelphia. They raided, they pillaged, and, what was even worse, they came to stay, ruling much of England, especially in the north. All of a sudden the list of English kings (most of whom were actually kings of smaller holdings like Mercia, Northumbria, or Wessex) stops being full of Egberts and starts in with Canutes and the like. Canute tells the waves to stop, and gets wet in the process. |

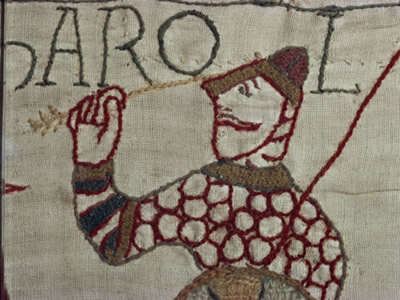

But those pesky Anglo-Saxons weren't going away, and when 1066 rolls around there is a dispute over whether Harold Godwinson, son of the great Wessex lord Godwin, ought to be king or whether Harold Hardrada (a Viking) or William of Normandy, (a Frenchified Viking), ought to be king. Harold Godwinson had to run up north and defeat Harold Hardrada, and then run down south for the Battle of Hastings, which for some reason didn't take place at Hastings but at Battle. Go figure. Why they did not call it the Hastings of Battle, no one can guess. |  The Bayeux Tapestry: "You'll put your eye out, kid!" |

Geoffrey Chaucer: "Hey, pull my finger!" | The Battle of Hastings ended with the French Vikings (Normans) in control, and this little episode led to our English language being the weird French/German hybrid which it remains to this day. The Germans left us most of the good cuss words and all the plain-talkin' stuff, but if prevarication or obfuscation is what you desire, French-rooted verbiage is veritably the vocabulary pour vous. This is true today, or, as one might say, "veritable even at present." For a couple of centuries to come, the nobility would speak French and the peasantry English, giving rise to some hideously over-simplified politics in Robin Hood books, plays and films. But by the thirteenth century, the incomprehensible-to-our-ears Anglo-Saxon language (opening line of Beowulf: "Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon.") had been transformed into Chaucer's tongue--a bit difficult to read in the original, but broadly understandable, and full of jokes about farting. |

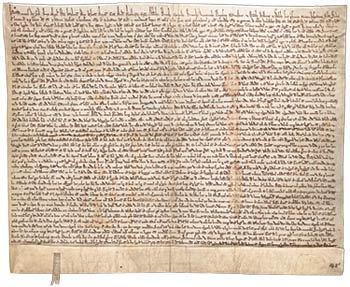

Oh, the medieval times. A mess of Henries, one Edward to hammer the Scots, one to hammer (or be hammered by--history is vague on this) Piers Gaveston, and one to bring the hammer down on his dad. The earliest precursors of Parliament, and the common law, begin back here and the British practice of making someone king, convincing him he has absolute power, and them humbling him (John, what with the Magna Carta and all) or ejecting and/or murdering him (Edward II, what with the not-suitable-for-family-reading bit), originates here as well. The British kings are sometimes indifferent to England (Richard the Lionhearted), sometimes crap (his brother John), and sometimes very interested in England and decent at the job after all. After a couple of centuries they stop speaking French, and manage to lose all of their French lands. British cooking never recovers. |  Dang ole Magna Carta |

| The Wars of the Roses come along, and it's pretty much a Fox Network episode of "King Swap" for a while. Then the Yorkists manage to do themselves in, what with Richard III murdering the princes in the Tower, seizing the throne, and writing "The Goodbye Girl." Henry Tudor, grandson of a Welshman who married Henry V's widow, defeats Richard at Bosworth and wins the all-time prize for "worst claim to the throne of any reigning monarch." But it sticks, he becomes Henry VII, and the Tudor period, characterized by an emphasis on coupes rather than family sedans, begins. Henry VIII becomes history's most famous mass-consumer of women and unwitting dupe of the Reformation, Edward VI tries to will the throne to Jane Grey and gets her killed in the deal, Mary becomes queen and, in the furtherance of the Catholic cause, kills so many Protestants that the English nation never goes Catholic again, and Elizabeth makes a damned fine capper to the whole thing and, with the help of a bit of wind, defeats the Spanish Armada. And no, that's not one of Chaucer's fart jokes. |

So, it's off to the Stuarts, not the wisest of kings. Their progenitor, Mary Queen of Scots, managed to get Elizabeth to kill her, so on Elizabeth's death the throne goes to Mary's son James. James has the King James bible written (swiping considerable work from Tyndale, who'd been burned alive for translating it into English), then passes the kingdom to Charles I, who does such a good job of running it that he is executed for treason against himself. Oliver Cromwell and a cadre of puritans and military types run things for a while, and they match Charles I in wise government, so much so that Charles II gets invited home to take over, which is the sort of job offer one doesn't turn down. Charles II is the genius of the Stuarts, and actually manages to keep a complex array of competing forces in balance and not get executed, even while being secretly Catholic, and passes the whole shebang to his brother, the publicly-Catholic James II. James II had all the cleverness of his father Charles I, unfortunately, leading to the end of the Stuarts in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, where Parliament kicked out James and invited William of Orange (third in line behind James for the throne, and married to Mary, James' daughter and first in line) in. |  A Stewart monarch, but, oddly, not a Stuart one. |

| James' supporters hang in there for another century or so, until the French-raised "Bonnie Prince Charlie" puts the final stop to the Jacobite cause by getting a lot of Scots killed in a harebrained scheme to retake the throne. It is now thought that Charles Stuart was the inspiration for the Al Franken character, Stuart Smalley. Historians now largely agree that as he sailed from France, instead of saying something like "the die is cast" that would be re-quoted millions of times, he said something which, translated out of French Scots, means something more like "I'm going to be King of Britain now, because I'm good enough, I'm smart enough, and doggone it, people like me." They didn't. |

After Queen Anne (Mary's little sister), with an anti-Catholic rule on the succession having been arrived at by Parliament, the whole deal passes over about fifty Catholic claimants to one incredibly lucky, and Protestant, German prince, George I, the Elector of Hanover. The Georges go on for a while, through "mad" King George III and "snippy" King George IV, and pretty soon it's time for Queen Victoria who stays on the throne for a long damned time. Does she have Prince Albert in a can? History does not say, as the telephone prank would not be invented for some years to come. "Watson, is your refrigerator running?" Speaking of Watson, Sherlock Holmes doesn't exist around this time but has some splendid adventures. |  |

| And then comes the 20th century. Victoria's nephew Kaiser Wilhelm makes an error of judgment which causes a generation of young men all across Europe to die horrible deaths as nobody in charge of any national army can think of anything better to do against a machine gun other than to charge it on foot across a large, shell-pockmarked open field. This makes for easily the most depressing of all Blackadder episodes. Lloyd George, Woodrow Wilson and Clemenceau make a series of boo-boos at Paris and Versailles and set the stage for the next war. In the Second World War the Germans nearly destroy Britain, and after the Second World War the Labour Party nearly finishes the job under Clement Attlee. Then Margaret Thatcher, the Sex Pistols, Bush's poodle, Brexit and the magically-appearing-and-disappearing Tory majority, and you're pretty much up to the present. |

The Britain that emerges is a strange place. Do mind the gap between the train and the platform. |  |